Appreciating Ravindra Randeniya’s Multi-Faceted Career-by Uditha Devapriya

Source:Thuppahis

August 2025, where the title runs thus: “Ravindra Randeniya: Sri Lankan Actor, South Asian Artist”

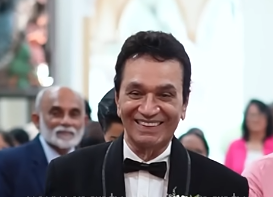

Ravindra (left) & Dilip Kumar (right) in New Delhi…Courtesy Ravindra Randeniya

In South Asia, cinema is more than an art: it is a way of life. Sri Lanka is no exception. Despite its size, the small island-state boasts of a film industry that has won renown abroad, even if it is facing a downturn today. At its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, Sri Lankan films travelled to New Delhi, Tehran, Tashkent, even Cannes and New York.

In 1977, one such film made its way to New Delhi. This was Siripala saha Ranmenika (Siripala and Ranmenika). Based on the life and death of one of Sri Lanka’s most popular yet controversial gangsters, the film had been a hit at the box-office back home.

In India the film was received well, with a reception and delegation which included not just Dilip Kumar and Satyajit Ray, but also the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Satyajit Ray in particular had been taken up by the film, and had commented as such to Malini Fonseka, Sri Lanka’s leading actress, who played the female lead. The director, Amarnath Jayatileka, was known well to Ray: in 1961, he had gone to Calcutta to study cinema, eventually winding up under India’s most internationally lauded filmmaker.

In the context of the Sri Lankan and even South Asian cinema, Siripala saha Ranmenika represented a new kind of film and featured a different type of hero. As the protagonist, Siripala elicited both sympathy and fear from audiences. People were put off by him, but also moved to sympathy for him.

This had a lot to do with his character. The real-life Siripala, who was later put on death row, had quite a colorful figure, escaping from prison more than once. His hanging led to an outcry and a moratorium on executions in Sri Lanka. Like Bonnie and Clyde and Phoolan Devi, he soon became immortalized in songs, poems, articles – and films.

Siripala saha Ranmenika immortalized the man. It also immortalized the actor playing him, Ravindra Randeniya, who had by how become established as a leading actor and one of the most sought-after names in the Sri Lankan film industry.

Ravindra with Malini Fonseka, Siripala saha Ranmenika, 1977

Courtesy Ravindra Randeniya

For Ravindra, Siripala saha Ranmenika became a watershed, ensuring both popularity and critical appeal for him. It won him his first award, as Best Actor at the OCIC Awards in 1978, organized by the World Catholic Association for Communication or SIGNIS.

This couldn’t have come at a better time. By this point, the Sri Lankan cinema had reached its peak. In 1970, a year before Ravindra entered the industry, the country’s pre-eminent filmmaker Lester James Peries directed Nidhanaya, which critics today consider to be the greatest Sri Lankan film ever made. Peries’s film had made waves at the Venice Film Festival, though its producers failed to make a bid for the Academy Awards.

Economically, these were difficult years. Writing to the New York Times in 1970, when the country was called Ceylon, Sydney Schanberg – of Killing Fields fame – observed how film and theatre had picked up despite the most impossible odds. One playwright, for instance, worked in a government office at “430 rupees a month, which is just over $70.”

“The plays make little or no money. The longest consecutive run is about a week, although the well‐received ones are continually restaged.”

Making matters worse, in 1971, a year before it became a Republic, Sri Lanka witnessed its first mass-scale youth uprising. It was swiftly put down by the government, but it had massive repercussions on local society and politics.

Newspaper headline from 1971 ….Courtesy LMD and National Archives of Sri Lanka

This was immediately followed by the 1973 oil crisis. The resulting slump compelled the government to enforce rationing, putting a further strain on the population.

And yet, despite these privations, the film industry flourished. This had much to do with the policies being enforced in that sector. In 1970, a socialist government had come to power promising to look into the problems of the industry and to promote local cinema. Two years later, in line with its pledge, it set up a National Film Corporation.

Under its first General Manager, D. B. Nihalsinha, the Corporation implemented reforms that centralized the production, distribution, and exhibition of films. These led to an increase in attendance figures, peaking at 74.9 million in 1979.

These policies led to an increase in the number of films, mainly through a comprehensive support scheme that granted approval for scripts and provided directors with concessionary loans. The loans fell under three categories, and were financed jointly by the State-run People’s Bank and the Film Corporation. By tying these loans to the quality of the script, the Corporation squared the circle, ensuring more films of better quality.

When a new government committed to free markets, free trade, and economic liberalization won the general election in 1977, these policies were abandoned. Yet by then, they had helped promote the cinema on an international scale. In other words, long before Muttiah Muralitharan and Arjuna Ranatunga broke through to the world of international test cricket, films were putting the country on the map.

Partly thanks to these developments, a new generation of actors made their way to the top. As in India, where the likes of Dilip Kumar were giving way to Amitabh Bachchan, this reflected a shift in attitudes among the youth, a radicalization of the latter.

The 1970s, in that sense, marked Sri Lanka’s counterculture moment, one could say its Nouvelle Vague. Young directors were experimenting with different styles and tackling controversial themes. Through the National Film Corporation, the government sought to encourage their efforts. Such policies pushed a group of radical critics and film buffs, many of them university students, to enter the field.

These radicals exhibited a sharp awareness of their world, the changes that were sweeping through their society. Many of their films – to give two examples, The Wasps Are Here (1977) and Grasshoppers (1979) – found their way to festivals in India and Western countries. As they won awards and accolades, they brought fame and recognition for their actors. It was this set of actors that Ravindra Randeniya came to represent, and lead.

………………………………………………

Ravindra Randeniya was born on June 5, 1945, to a middle-class Sinhala family in Kelaniya, a village located around 10 kilometers from the capital Colombo. He was the second child in a family of four brothers and two sisters. His father was a businessman who ran a leading brass company in the country. His mother was a housewife.

St Benedict’s College, undated

Courtesy “Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon” (1907)

In his early years, Ravindra was sent to a church-run school close to home. Later he was sent to Sri Lanka’s oldest Catholic school – the family were all devout Catholics – St Benedict’s College, in Colombo. There, he gained an interest in literature and the arts, an interest that survived and, in a way, transcended his ambition to become a doctor.

Owing to certain circumstances, he could not pursue his medical ambitions. In 1965, he interrupted his studies to join his father’s business and to work under him.

These were years of artistic ferment in Sri Lanka. In 1956, when Ravindra was in his second year in Colombo, an election brought to power a nationalist government whose policies, including the nationalization of foreign businesses, oversaw the disintegration of the colonial order. It was this order that Ravindra had confronted in Colombo.

These developments gave political expression to a cultural revival. That empowered a new generation of novelists, poets, painters, and, most importantly for Ravindra, filmmakers and playwrights. It led to the growth of a bilingual cultural intelligentsia, the formation of independent theatre groups, and an impetus to establish film and theatre schools. All this would have a profound bearing on Ravindra.

In 1969, Ravindra saw an advertisement in a newspaper asking those interested to apply for a theatre school in Colombo. It was called the Lionel Wendt Theatre Workshop, and it was to be overseen by some of the country’s leading artists and scholars.

By now he was frequently watching plays and films. He did not really want to be an actor. Yet he felt intrigued. So he applied for the workshop. Eventually, he got in.

Over the next three years, Ravindra attended class after class, picking up the intricacies of his craft. In 1971, right before receiving a Diploma, he embarked on his film career.

From the beginning, Ravindra refused to be selective. He wanted to try out different parts, to take on different characters. More than anything, he wanted to broaden his range. “An actor’s duty,” he argued, “is to bury himself under his characters, rather than submerge them under his personality.” That became his underlying philosophy.

It had been part of his training at the Workshop as well. It held him in good stead when he began getting one offer after another. As he himself puts it, these offers were “hot properties”, which most actors would get only after five or six years in the industry. They were all overseen by leading directors, who gave him the push he needed.

Among these were Lester James Peries (with whom he worked on three films during that decade), Manik Sandrasagara (two films), and Vijaya Dharma Sri (who gave him what can be considered as his breakthrough role, a well-meaning but somewhat immature lover who falls for a married woman in Duhulu Malak, 1976). Lester, in particular, was at the peak of his career. In selecting a newcomer for his films, he essentially committed a leap of faith. “After Lester chose me, I never had to look back,” Ravindra recalls.

By the time of Siripala saha Ranmenika, he had been recognized in the national press and even travelled abroad. His approach, of not being selective and not settling down to stereotypical roles, paid off: soon he was getting different characters, from the good to the bad to the ambivalent. More importantly, he was winning awards for them.

By Ravindra’s own estimation, the 1980s marked his most productive period. Towards the end of that decade, he was taking part in two, three, sometimes four films a year.

“Dadayama” (Vasantha Obeyesekere, 1983) … Courtesy Vasantha Obeyesekere

These films exemplified his repertoire. They include lovers and husbands (Aradhana, 1981), tribal chiefs (Sathweni Dawasa, 1981), murderers and womanizers (Dadayama, 1983, and Maya, 1984), famers and cultivators (Maldeniye Simion, 1986, and Sagara Jalaya, 1988), and mutes and cripples (Janelaya, 1987, and Siri Medura, 1989). What distinguishes them is their lack of uniformity. That fit in with his wishes: he did not want a signature role.

Soon these brought him into the notice of foreign filmmakers, and got him onboard several foreign productions. They included not one but two biopics on Mother Theresa, “one with Geraldine Chaplin, the other with Olivia Hussey.”

Decades earlier, in 1976, while playing a supporting role in a British-Sri Lankan production, The God King, he had met Ben Kingsley. By the time he met Geraldine Chaplin and Olivia Hussey, he had got to work alongside the French actress Veronique Jannot in a film called L’Enfant des Rues (Street Child, 1998). He also got to meet Indian actors who had put their country on the world map, including Roshan Seth.

As with many South Asian actors, Ravindra found himself in politics. From 2000 to 2004, he served first as a National List and then an elected MP, the latter as a representative from his district, Gampaha. He got into politics hoping to address and resolve the problems of the film industry. Eventually, however, he realized that it was distancing him from his profession. When his party lost a crucial election in 2004, he thus left politics altogether, vowing not to return. Except for a brief stint as a presidential advisor, he did good by that promise. He has been acting ever since: his most recent film, Ridi Seenu, came out in 2024.

………………………………………………

As of 2025, Ravindra has taken part in close to 120 films. These encompass diverse genres, from romantic dramas to murder mysteries to psychological thrillers. For a Sri Lankan actor, this is an astonishing range. Yet while it reflects well on him, it underlies the tremendous potential the Sri Lankan cinema has, which owing to various factors – not least of which the present economic crisis – it has never been able to realize in full. In the 1960s and 1970s, well into the 1980s and 1990s, Sri Lanka became a top destination for foreign productions, including from Hollywood, largely thanks to the efforts of the American-trained director and producer Chandran Rutnam. This is no longer the case today.

Courtesy Prem Dissanayake (Printer)

The recipient of several major accolades – including from two pre-eminent national awards ceremonies, the Sarasaviya and the Presidential – Ravindra Randeniya figured in at the forefront of these developments. His achievements crisscross several generations, from my grandparents to me to Generation Zers after me. There are few actors without whom you cannot talk about the Sri Lankan cinema. Ravindra is one of them.

On Wednesday, 5 June 2024, Ravindra turned 79. That year marked 50 years since he began his career: his debut film was Kalyani Ganga, where he played a supporting role. For this occasion, a group of actors, artistes, relatives, and well-wishers got together, formed a committee, and organized a felicitation ceremony. Taking audiences through his 50 years in the cinema, it featured the launch of two biographies, one in Sinhala, authored by the Sri Lankan film critic Gamini Weragama, and the other in English, authored by me.

This was not a typical felicitation ceremony. Held at Colombo’s most popular convention center, the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall or BMICH, it saw a galaxy of actors and actresses, politicians and officials, and fans and well-wishers. One of my friends, Indunil, put it all in perspective: “The whole of Sri Lankan cinema was there last night.” Ravindra agreed: “In a nutshell, that is what the event was.”

With Amitabh Bachchan. Courtesy Ravindra Randeniya

As one actor after another got onstage and reflected on Ravindra’s life, his work, and his character, though, I reflected on what the Sri Lankan cinema had been and what it could have become. Seeing the deterioration that has crept into it – a deterioration that has not seeped into other film industries in South Asia, yet – I wanted

“This is a living treasure,” someone described Ravindra during the event. A living monument or testament would be more apt: both to the possibilities of the Sri Lankan cinema and to the years and decades of downturns it has undergone. “In Sri Lanka, before cricket, there was cinema,” Ravindra noted. Today even cricket seems to have come down. It is futile to dwell on the past and present, yes. Yet it is imperative to think of the future. In charting a path for the cinema, Sri Lanka may need another Ravindra, just as cricket may need another Arjuna Ranatunga or Muttiah Muralitharan. But just where is he?

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, analyst, and researcher from Sri Lanka who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com. He is the Chief International Relations Analyst at Factum, an Asia-Pacific focused foreign policy think tank based in Colombo. He is also one of two leads at U & U, an informal art and culture research initiative.